The construction of the piano and its regulation, page 3

I have presented a substantial lecture on the history, the tuning and regulation of the piano. It's around 4 hours long and contains many music examples: the sound of Cristofori's, Mozart's, Beethoven's, Chopin's and Liszt's pianos. Many more sound examples and pictures of tunings are included. The material below is only a small fraction of the complete lecture.

The Italian harpsichord maker Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655–1731) was born in Padua, and employed 1688 in Florence by Prince Ferdinand di Medici. Cristofori was the inventor of the piano – he called it the "gravicembalo col piano e forte" (large harpsichord with soft and loud). This name was later changed to pianoforte or fortepiano, and eventually to piano.

Usually, the date for the "birth" of the piano is set to 1709, when an article by Scipione Maffei about the instrument was printed. But we know now from an inventory (to the right) made in 1700 of the Medici family, that an instrument of this type was already present at that time. So the true birth date for the piano is somewhere in the late 1690’s.

Oddly enough, the essence of the mechanism and concept of the piano was nearly complete right from the outset. The same basic concept is still in use today! Only a few things have been added.

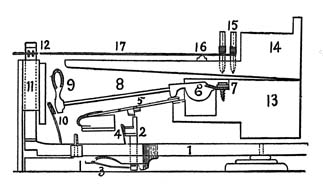

This is the last action constructed by Cristofori in 1720.

It has an escape action still in use today.

The only innovation in the modern Steinway action – aside from larger and more refined

parts – is the double repetition lever and felt hammers instead of leather hammers.

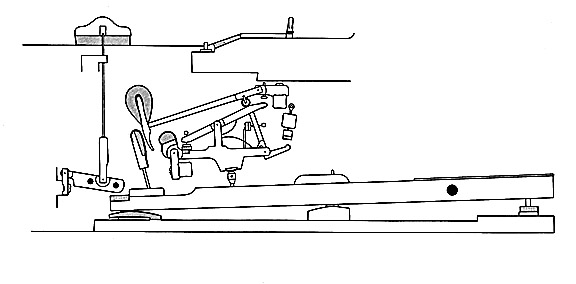

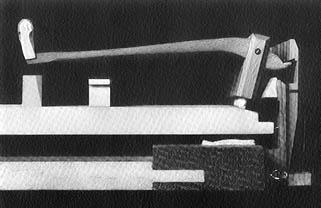

This is a picture taken from a museum in Florence, of a key frame

with a complete action made by Cristofori.

This is the only playable Cristofori Pianoforte of the three that still exists. It was made in 1720

and is housed in New York at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Cristofori built about 20 instruments.

They were not appreciated by musicians and Cristofori went back to building harpsichords in his last years.

This pianoforte is at the Music Instrument Museum in Leipzig.

This third surviving pianoforte can be seen at

Museo degli Instrumenti, Musicali in Rome.

The history of the piano continues in Germany 1736 when Gottfried Silbermann (1683–1753) re-invented the piano. There is a very famous story about J. S. Bach trying out the instrument in 1745. He liked the sound but found it difficult and unresponsive to play on. Silbermann read the article by Scipione Maffei about Cristofori's instrument from 1709 – it wasn’t translated until 1747; slow communication even for that time... Silbermann then changed the action in his piano to a refined version of Cristofori's and now it got Bach's approval. Bach even became the local representative for Silbermann’s fortepiano.

From Silbermann's workshop two piano building schools developed: the German and the English.

In 1773 Johann Andreas Stein (1728–1792), one of Silbermann's most talented students, invented the "Mozart-clavier" with a special and also simpler action called the "Viennese action". This instrument was not further developed and after Mozart it was soon forgotten. Mozart's personal piano (the picture above), was built by Anton Walter in the early 1780's and is still playable.

In the English School the foremost builder was John Broadwood. He developed the piano and increased its dynamic range by equipping it with higher string tensions. He rearranged the layout of the wooden bridges on the soundboard by introducing a separate bass bridge and expanded the compass to six octaves by adding half an octave in the treble and half an octave in the bass. He also improved the "hammer blow mechanics" so the hammer could be swung with greater force towards the strings. Usually referred to as "the English action" it demanded greater strength to play and made fast passages more difficult to perform. In his later years, Broadwood used a small iron frame to reinforce the wooden frame. Beethoven received a Grand Piano from Broadwood as a present and this instrument is still playable today.

Another very important event was the marriage of the barely 17-year old princess Charlotte de Meckenburg-Strelitz in 1761 to king George III of Britain. Charlotte was very interested in playing the piano and had Johann Sebastian Bach's son, Johann Christian Bach as a teacher. From this time stems the tradition that every "well bought up" girl should have musical training, and the ability to play the piano was a natural part of this education. Of course when there is a demand for something, there will also be builders that will profit from it. Johann Zumpe managed to mass produce a simple instrument – a small square piano – that was sold to everyone.

The development of the piano could, in simple terms, be described as the search for a richer, more voluminous tone combined with a more responsive and reliable action, allowing for the quick repetition of the notes as required by virtuoso pianists.

Piano history continues in France when Sebastian Erard, between 1808 and 1821 developed "the double escapement" mechanism. He added springs and levers, allowing the hammer to rebound only at half the initial distance. This action was later modified and improved by Herz. Today it is in use in all Grand Pianos. In 1826, felt hammers (instead of leather) were tried for the first time by an ingenious piano maker in Paris named Pape.

The wooden frame was, over time, reinforced with more and more iron, and in 1825 the complete cast iron plate was introduced by the American piano maker Babcock for upright pianos and a one piece cast iron for Grand Piano frames by Chickering in the 1840’s.

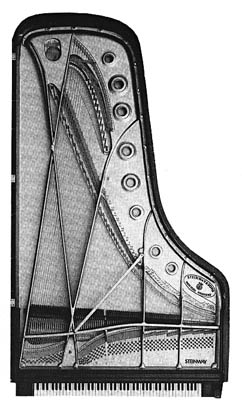

Some of the last improvements were made by Steinway in New York. The introduction of the over stringing – spreading the strings fan-like across the instrument – was the ultimate solution for the layout of the strings. Initially they had been strung parallel to each other. With this new distribution the bass strings could be longer and have less inharmonicity without a corresponding lengthening of the instrument.

At the Paris exhibition 1867, Theodore Steinway displayed a Grand Piano that had an increased string tension that corresponds with the present figure of 21.272 N at 440 Hz.

After the second World War the piano makers could work with newly improved glues. A further improvement was kilning, or the controlled drying of wood using heat, steam and ventilation. With this process timber can now be dried to lower moisture contents than was possible before 1939. Kilning enables soundboards, tuning planks and casework to withstand the effects of central heating in houses. Modern soundboards are unlikely to split and tuning pins to work loose, or casework to crack.

The building of a Grand Piano Page 4